How migrants stay in touch

How migrants stay in touch

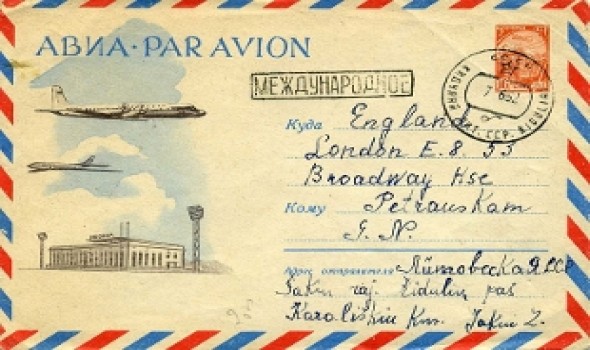

Most migrants yearn to maintain contact with their families, friends and homelands. But how they do so depends on the changing technologies at their disposal. Not so long ago illiterate migrants had to go to a friend or professional letter-writer. The result tended to be formal and impersonal, because it’s not easy – and sometimes not safe – to express your feelings and divulge your secrets via a third party. Most people are too inhibited and cautious even to try. And for literate senders and receivers there’s the problem of time-lapse. An elderly man consulted about this article recalled dashing off angry letters, or writing when he was feeling low and weeks later being puzzled by a return letter anxiously inquiring about his illness: he had long forgotten about the bad day that provoked his original letter. A well-written letter, on the other hand, would kindle love and affection and be a valued keepsake. A cack-handed journalist friend, Daniel, also remembers the problems he experienced with “blueys”, those deliberately flimsy aerograms on which you wrote and which, when folded along two dotted lines, were transformed into an envelope. Handy, except that he was so worried about them coming unstuck that he would over-glue them to the point at which the paste would ooze out, making swathes of the letter unreadable. Louise remembers how letters from her mother contained recipes for food, wedding invitations and notices of funerals - “and she always included accounts of what was eaten at these celebrations or funerals.” Her fondest memory is of letters containing autumn leaves collected by her mother while walking in the woods in Michigan. Phones were transformative, but were fixed to the spot, cumbersome, expensive and often engaged. Internationally, calls often needed an operator who had to be asked to dial the number and then periodically cajoled, if not bribed, to actually make the call. Connection established, the operator might accidentally cut you off. Frequently there was a time-lag and an echo on the line that made conversation stilted, with silences as each party waited for the other to speak. Phones were, in a word, frustrating. And scarce. For many people, keeping in touch meant calling the only phone in the district or a nearby shop and asking whoever answered to send a message to your parents to come to the phone in two hours, when you would try again. Louise remembers the awkwardness: “Telephone calls were very important, but very expensive and so they were spent repeatedly saying ‘Louise is on the ‘phone. Hurry, hurry’ or ‘Can you hear me? Can you hear me?’ “ By this time, the three-minute call was over. We hurriedly said ‘I love you.’ We didn’t ‘phone again for months.” Her parents also taped music and news from the radio and TV. Now Louise’s own daughter is studying abroad: “We communicate by telephone because they are now less expensive and by Skype. Skype means that I can find out all the odd things my mother worried about: if my daughter is eating enough, if she is ill. So becoming a mother and Skype have changed my life.” For some, cassette tapes were also transformative. In Lebanon, remembers Nazek, whenever someone announced they were going abroad, they would be asked to deliver a tape. Requests were never turned down. “Almost everyone who travelled carried tapes to different families they did not know,” she recalls. “Each tape was accompanied by a note giving the name and telephone number of its recipient so they could be contacted and asked to collect the precious package. A letter introducing the tape acted as the equivalent of an email to an attachment. “News would reach you that someone was travelling on a certain day and you would work out how long you had to make your tape. The tape would stay in the tape recorder until the day of delivery to the carrier and the whole family would be informed that a tape was being prepared so they could plan to make time to speak on it. Each family member visiting your home would record a message. Even neighbours, friends and friends of friends would feel obliged to leave a message saying something, anything!” During the Lebanon war, hundreds of thousands of tapes were flying in and out of the country. “I would listen to the tape my sisters sent me from Beirut several times a day,” remembers Nazek. “It was not always important what they said. Hearing their voices and their laughter was my assurance. No letters or words could replace their voices. I still have some of those tapes.” Sara recalls how, in another Arab country, a friend told her that her new husband sent her very personal taped messages. She left one of the tapes in the car cassette player. It was stolen and copied and became a huge hit! Tapes – later followed by Super8 films - were finally immortalised in a documentary, I Is For India, made by the daughter of an Indian doctor who migrated to England in 1965. She based the film on the home movies and reel-to-reel tape recordings he sent home. As the family grows up and the temporary sojourn in England turns to years, Dr Yash Pal Suri talks longingly of keeping in touch and of meeting up again, about the family’s decision to stay on, and about the way the natives wilfully mispronounce his name. Years later, the divided family divides again, as eldest daughter decides to make a fresh start in Australia. The pain of the Suris’ sadness is again captured on camera, and the poignancy reaches breaking point when Dr Suri’s films and tapes are replaced by a jerky computer link between UK and Australia and daughter admits her new job is not working out well. Through all these technological developments, of course, there were photographs. The memories of one Iranian in Britain sum up the experience of millions: “When I graduated I had two photos taken to send to my parents. Shortly after they received the photos my father, who did not usually demonstrate emotions, wrote me a moving letter saying that those were the most beautiful photos he had ever seen. “Himself a migrant, he had worked since the age of 14 supporting a family with no chance of getting education, paying for my education by sheer hard work. To him, this was the fruit of his labour. “Years later, after I had lost my father, I was able to go home. I went into my parents’ bedroom and saw the very same photos on their bedside tables. Now each time I look at them it all comes rushing back to me.” Today it’s easier. Shayna, an American living in Canada, talks to people “back home” many times a day, by text, email and phone, sometimes for at least an hour. She Skypes a lot, but also still sends cards to friends. The ease of communication is contagious. “I moved away from my mother at the age of nine so I have years of experience communicating,” she says. ”About five years ago, my mom surprised me because at the age of 59 she taught herself to text – she started texting me non-stop! She has become a text addict.” And though new technology seems to have spread to every corner of the globe, Ernest says that “People from back home in Cameroon don’t really use internet as over here, and I remember when my family saw me on the screen for the first time since I had travelled. Some of them could not believe their eyes: they were shouting and screaming loudly, calling my name to see if it was really me.” Finally, a word of caution from Sara, who remembers the inconvenience of going to a poste restante office to see if anyone had written, and of making sure the postal clerk affixed the stamp to your letter rather than pocketing the money. She is not in favour of returning to the days when you had to wait weeks to hear from someone you loved - but counsels: “If you are using email, smartphone or Skype it’s possible you never leave your world - or computer - behind and you engage less with the new world around you.” With input from Sahar Ehsas