It's back to school at the weekend

It's back to school at the weekend

There are between 3,000 and 5,000 Saturday (or complementary) schools in the UK catering for people from a specific nationality.

Organised through cultural groups and associations, they offer supplementary education in core curriculum subjects, languages, culture and religious topics to children in mainstream education.

Emma Padner, a Glasgow-based freelance journalist who specialises in migration and gender, visited three of them.

Saadi Glasgow Iranian School

* Eight years after coming to Scotland as an asylum seeker, Shahnaz Kaiedpour jumped at the opportunity to be back in a classroom, teaching young people in Glasgow at the Saadi Persian School.

“I am pleased that I have a chance to help Iranian children to learn about their family’s culture and about the different traditions from Iran,” she says.

Kaiedpour taught maths in Iran for 17 years. She fled In 2008 with her two young sons. Now she teaches children between the ages of 3 and 13 on Saturdays.

The school is one of many ethnic minority schools in the city sharing the goal of teaching culture, language and traditions from countries of origin to young migrants or children of migrants. +++++Many cultural schools hold classes on Saturdays and function as a small community hub for migrants.

School is split into two shifts, 1-3pm and 3.30-5.30pm. The children come from Persian or mixed families, though a number of Scottish adults take Persian lessons, too, online or in-person.

Some Scottish students want to learn Persian because they travelled to Iran or would like to do so or have Iranian relatives or friends. A few are simply interested in learning languages.

The Iran-born population in the Glasgow City Council area was 2,647, according to the 2022 Scottish census. After protests erupted in Iran following the death in police custody of a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa Amini, in September 2022, the number of Iranians seeking asylum in the UK and other countries rose.

“Being a part of Saadi Persian School is not only rewarding for the students but also for me as a teacher,” says Kaiedpour. “The joy of seeing children learn, grow, and express themselves in their mother tongue is truly fulfilling.”

They learn to read or expand their vocabulary, she says, and “between each lesson they have fun and also take books home. Sometimes we watch Persian movies.”

Marzieh Dastjerdi is a parent who hasn’t been able to return to Iran since she came to Scotland in 2007. She claimed asylum in the UK and the family were sent to Glasgow. She said her two children, now aged 17 and 15, benefitted academically and socially through attending the Glasgow Saadi School for four years.

“It was always important to me that my children know what their motherland is like. Unfortunately, I have never had the chance to take them to Iran, where they would get to know their culture and traditions,” she says. “I decided, therefore, to introduce them to reading and writing Farsi in Glasgow.”

“My children have not only learned their mother tongue, but they have also gained a greater understanding of the customs of our culture and made friends with other Iranian children,” says Dastjerdi. “Without the support of my children’s kind teacher, this would have been much harder to achieve.”

The school runs special events for festivals such as Yalda night, celebrated on the winter solstice; Nowruz, the Persian New Year; and Christmas. Similarities and differences between cultures are explained at these events, which also help students appreciate their heritage.

Kaiedpour says such celebrations “not only teach cultural traditions but also foster a sense of community and belonging among the students. To gain more understanding of culture we ask them to draw, write and talk about the events.”

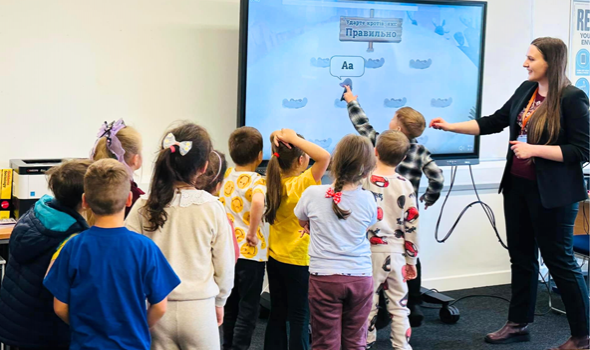

St Mary’s Ukrainian School Glasgow

* St. Mary's Ukrainian School was established in London more than 60 years ago, catering for Ukrainians who came to Britain after the Second World War.

Now a sister school in Glasgow is helping educate some of the 25,000 Ukrainians offered sanctuary by the Scottish government after the outbreak of war the Russia-Ukraine war.

One of those refugees, Nataliya Lyalyuk, is putting her 18 years teaching experience to work at the new school.

She arrived in Scotland in 2022 with her two children, her mother and their dog. Her husband stayed behind, and her children have not seen him for more than two years.

Lyalyuk noticed that Ukrainians were struggling in Scottish schools because of language difficulties.

“Glasgow welcomed a lot of families from Ukraine, especially with children, and school helps them carry on with schooling from Ukraine as well as learning the language,” Lyalyuk says through her 17-year-old son, Nazarii, who translated during our interview. “It’s very helpful to adjust in a new society, to communicate in our native language.”

St. Mary’s Glasgow follows the Ukrainian education system, she says, emphasising the importance of students adapting to the host country’s education system while continuing to study their home country’s language and literature.

Ukrainian schools abroad are also cultural hubs: “They perform an important mission, which is to transfer knowledge about the history and traditions of Ukraine, and contribute to the formation of the cultural identity of students. This helps Ukrainian children abroad to understand their roots and feel part of a large Ukrainian family.”

The school is run by a team of 10 Ukrainians, three of whom are volunteers.

A few pupils have disabilities, and are given extra attention by the teaching assistants.

Every Saturday they have three groups for lessons in Ukrainian language, literature, history and general knowledge. Classes run from 9.30am to 12.30pm.

“The most important part in our job is that we can see the children smile,” says Lyalyuk. “Their smiles persuade us to do our best, to provide the best educational services.”

She points out that many Ukrainian refugees suffer from war trauma, and a specialist school enables pupils to talk to people their own age and feel more comfortable in their new home.

In addition, some Ukrainian students at the school were born in Scotland but want to learn their parents’ language.

The school is “like a small Ukrainian community between children and their parents, helping them to be more comfortable in a new country, communicate in their native language and remember traditions from home,” she says.

“We are happy that we were able to unite into a single school community to celebrate all Ukrainian holidays together, including Ukrainian Independence Day, Flag Day, Defender of Ukraine Day,” Lyaluk adds. “We are also happy to see the Scots at our Varenika holiday, celebrate Christmas together and paint Ukrainian wooden toys.”

Nazarii studied English when he arrived [here/in the country?in Glasgiow?], has been accepted to study international relations at The University of Edinburgh and is the first Ukrainian member of the Youth Parliament of Scotland.

“My mother worked in education in Ukraine for 18 years so she has a lot of knowledge and skills,” he says. “She is very very happy when she sees that people are coming to school to get knowledge and they smile.”

General Sosabowski Polish School Glasgow

* When Polish geography teacher Pawe? Pora?ski moved to the UK in 2005 he struggled to find teaching positions because his English wasn’t up to scratch.

He improved his English through college courses and in 2012 heard about job opportunities at the Polish School in Glasgow.

He is one of the three teachers who re-established the school in that year and is now the deputy head and supply teacher for Polish geography and history.

The 300-pupil school has 18 teachers and 12 volunteers. Demand is fairly constant, because In 2020 there were 92,000 Poles living in Scotland, making them the country’s biggest non-British nationality, according to the National Records of Scotland.

Poles are more widely spread than most other minority groups in Scotland, with more than half living outside the four city council areas. A handful of the school’s pupils live two-hours away, in places such as the Isle of Bute or Lochgoilhead.

The school, recently renamed after a famous Polish General, teaches Polish language for students aged 5 and above and Polish history and geography for the over-10s. Classes run every Saturday through the school year from 9.30am to 12:45pm. It hosts cultural and community events for Polish holidays and traditions.

Two of the current volunteers are former students of the school: one plans to become a teacher, says Pore?ski. This year’s GCSE students have been volunteering with younger students, too.

“Every teacher is extremely proud of their pupils' achievements,” he says. “The most fulfilling scenario is when pupils progress to be a volunteer in our school and then go on to university to become a teacher.”

When three former pupils started a Polish Scouting group in Glasgow, he recalls having wanted to start such a group himself, but he had always been busy with re-establishing the school: “When your former pupil achieves what you fail to achieve yourself, that’ll certainly make your day.”

Alan Korzeniowski, 18, attended the school for eight years after his parents moved here in 2007. He loved the school because it gave him the opportunity to meet other Poles and talk Polish.

“History became my favourite subject and maybe that's why now I love to deepen my knowledge of Polish history and World War II,” he says. “I have fond memories of the games I played with my friends, history lessons and the history club.”

He points to differences between Polish and Scottish education. While not wearing a uniform to Polish school made it feel relaxed, he found the teachers to be stricter than at Scottish schools.

Korzeniowski remembers the lessons as more interactive and team-based. It was more about using the Polish language to communicate than studying concepts, he says.

Later he learned about the culture, history, geography and “everything there was about being Polish”, he recalls..

As students got older, classes got smaller, he says, because some students became increasingly involved with Scottish school assignments, social life and extracurricular activities.