The mosque my great-great-grandmother built

The mosque my great-great-grandmother built

Woking is the site of a beautiful place of worship built by a remarkable woman. Ira Mathur, a Trinidadian who studied in Canada and England, tells its story and that of her visionary great great grandmother

When I was at university in London my grandmother, Shahnur Jehan Begum, wrote to me from Bangalore, India: “Go and see the first mosque built in Northern Europe. It was commissioned in 1889 by your great great grandmother, Nawab Sultan Jehan Begum of Bhopal. It is in Woking, not far from London.”

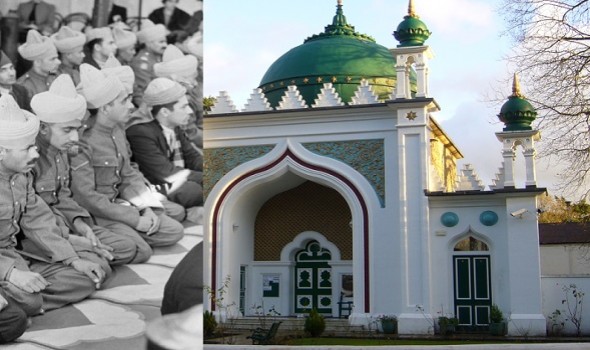

So I visited the Shah Jahan mosque in Oriental Road, 30 miles south-west of London, with its perfectly proportioned Mughal green and gold dome walls, green minarets, fountain and lawns.

Looking at its list of visiting dignitaries from the King of Saudi Arabia and the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, to Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and the Shah of Iran, I nearly wept.

My great great grandmother, Sultan Shahjahan Begum, was the begum (ruler) of Bhopal for two periods: 1844–60 (with her mother acting as regent), and 1868–1901. She was the last in a line of four women who ruled Bhopal for over a century.

She ruled in strict purdah. All her cars had curtains. She spoke to heads of state in full burka through a latticed screen. As a devout Muslim she felt it her duty to promote excellence as encouraged in the Quran.

Sultan Jahan collaborated with the British to help inoculate and vaccinate her subjects. She improved sanitation systems and cleaned up the water supply. She established a modern municipal system.

She advanced the emancipation of women by encouraging girls to attend school. She was the first president of the All-India Conference on Education and the first chancellor of the Muslim University of Aligarh and established an Executive and Legislative Council in 1922.

By the time she attended the Coronation of the King Emperor George V and Queen Empress Mary in London in 1911 she had developed a strong friendship with the British.

In 1926 she abdicated in favour of her favourite youngest son, Hamidullah Khan, instead of her eldest son – a move that was not only unheard of, but was illegal in princely states. She told everyone she would sail to England to speak to the King, George V, to get her favourite child installed as the Nawab.

Face to face with the King she ripped off her burka and reportedly said: “I have never shown any strange man my face. I removed my burka because I am your sister and you are my brother. I don’t want Nasuriallah, who is just crazy about hunting, nor Obaidullah, who has a hot temper, to be Nawab. I am abdicating for Hamidullah.”

The King protested that this was unprecedented and he could not allow it. She cried, she fainted, she made such a huge scene that he saw the only way to get rid of her was to agree.

She said the only reason she, a woman, was a ruler of Bhopal because Queen Victoria supported her.

In this way, this short, square begum dressed in a tent-like burka persuaded the King to change the law of succession by the sheer force of her nature.

Like previous begums, Sultan Jahan was passionate about architecture. She created her own walled mini-city, naming it Ahmadabad after her late husband and built several palaces.

Noor-us-Sabah was an opulent building crammed with European furniture and fittings. Qaser-e-Sultani had an exquisite Mogul garden called Zie-up-Abser built by the Nizam’s gardeners and filled with roses. They grew in the terrible heat because she installed with India’s first water pump.

Historians have marvelled over the dogged raw power of the begums of Bhopal long before women’s lib. They quietly ruled the second-largest state in pre-independence India and commanded politicians and princes. They created an infrastructure of waterworks, railways, a postal system and institutions for the arts and science.

All this happened because of the courage showed by the women rulers of Bhopal, and its intertwining engagement with the British. Although bloody and uneasy at times, the British dominion over India between 1858 and 1947 has resulted in interwoven histories between the two countries.

The Woking mosque is a legacy of those times and a testimony to the character of a remarkable woman.

Clifton Kawanga, a University of Westminster student from Malawi adds: When lawyer Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din arrived in London in 1912 to pursue his legal practice, he found that the condition of the mosque had deteriorated, acquired it and re-opened it.

After its restoration, it attracted royal visitors and British converts, including Lord Headley, who founded the British Muslim Society, and Marmaduke Pickthall, who provided the first and one of the most eloquent English translations of the Koran.

In 2006 it was estimated that about 1,500 worshippers attended the mosque every week while 3,000 turned up on special occasions.

The BBC reported that the mosque was deemed too small so warehouses at the back of the property were taken over and transformed into prayer halls. In 2011, a retired Brigadier, Muslim Salamat – who oversaw the mosque’s refurbishment– was given an Eminent Citizen award.

The mosque is a centre for community relations in Woking with schools around Surrey visiting it to educate children about Islam.

Photo of Shah Jahan Mosque, Woking, by R Haworth. Black and White photo is from 1941. It shows men of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps at prayer during the Eid ul Fitr ceremony in a tent, which has been set up alongside Woking Mosque.